what is the best way to educate teenage pregnancy intrapartum

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

The burden of adolescent motherhood and health consequences in Nepal

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth book xx, Article number:318 (2020) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Annually, 18 meg babies are built-in to mothers 18 years or less. Two thirds of these births accept place in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Due to social and biological factors, adolescent mothers have a higher gamble of adverse birth outcomes. We conducted this study to assess the incidence, risk factors, maternal and neonatal health consequences amidst adolescent mothers.

Methods

Nosotros conducted an observational study in 12 hospitals of Nepal for a period of 12 months. Patient medical record and semi-structured interviews were used to collect demographic information of mothers, intrapartum care and outcomes. The risks of agin birth outcomes among adolescent compared to adult mothers were assessed using multivariate logistic regression.

Results

During the study period, among the total 60,742 deliveries, 7.8% were adolescent mothers. Two third of the adolescent mothers were from disadvantaged ethnic groups, compared to half of developed mothers (66.1% vs 47.8%, p-value< 0.001). 1 tertiary of the boyish mothers did not have formal didactics, while one in nine adult mothers did not have formal education (32.6% vs fourteen.2%, p-value< 0.001). Compared to adult mothers, boyish mothers had higher odds of experiencing prolonged labour (aOR-1.56, 95% CI, 1.17–2.10, p-0.003), preterm nativity (aOR-1.twoscore, 95% CI, one.26–1.55, p < 0.001) and of having a baby being small-scale for gestational historic period (aOR-1.38, 95% CI 1.25–ane.52, p < 0.001). The odds of major malformation increased by more than two-fold in adolescent mothers compared to adult mothers (aOR-2.66, 95% CI 1.12–6.33, p-0.027).

Decision

Women from disadvantaged ethnic group take higher hazard of being pregnant during adolescent age. Boyish mothers were more probable to have prolonged labour, a preterm birth, modest for gestational age baby and major built malformation. Special attention to this loftier-chance grouping during pregnancy, labour and commitment is critical.

Background

In the Sustainable Development Goal era, the planet has witnessed the largest adolescent (10–19 years) cohort population in human being history. There are approximately 1.2 billion adolescents worldwide, with more than 85% living in low- and middle-income countries [1]. The boyish population has the potential to transform societies if provided with an enabling and empowering surroundings for a good for you life [ii, 3]. Adolescence is a menstruation of rapid brain evolution, alongside social, emotional and cognitive changes that prepare adolescents to transition to adulthood [four, 5]. The Lancet Commission for Adolescent Health and Wellbeing highlights the opportunities and challenges in improving adolescent health in the SDG era [half dozen, seven]. Among the key challenges for meliorate health of adolescents is the need to address boyish pregnancy and health outcomes of female parent and fetus.

In 2013, globally, 16 million girls between the ages of fifteen–19, and 2 1000000 girls under age 15, became pregnant [8]. There has even so been progress over the past 60 years. In the poorest regions of the globe, birth rates in 1950–55 averaged 170 births per 1000 amidst girls aged 15–19. In 2010 this was decreased to 106 per 1000 [9]. However, this nascence rate is still 4 times higher than in the loftier income regions of the world [9].

Co-ordinate to the United nations Population Fund (UNFPA), one third of all women between the ages twenty and 24 years report being married during adolescent menstruation [ten, eleven]. Globally and in Nepal, adolescent contraceptive prevalence rate is lower, and unmet need for contraception is greater for adolescents thank any other age group [12]. Contraception is one of the virtually effective ways to preclude pregnancy and in result reduce adverse outcomes amongst both adolescents and babies. Fifty-fifty though adolescent pregnancy is a global trouble, adolescents and young adults take been left behind in global health and social policy [13]. Given, the attending required for improving wellness and evolution of boyish, in September 2015, the Un Secretary-General's Global Strategy for Women's, Children's and Adolescents' Health provided an investment opportunity in boyish health and wellbeing [xiv, 15].

Pregnancy during the adolescent period entails considerable risk for complications during labour such as placental tear, obstruction and long-term consequences of obstetric fistulae [16]. Adolescent girls who go significant are more probable to be from a lower economic status than their peer, with poorer nutrition and full general health status. This in turn increases the likelihood of fetal, perinatal and maternal death and inability [17]. Farther, an unmarried pregnant adolescent is likely to face social discrimination and more than take a chance of violence, as pregnancy out of wedlock can a social stigma in low- and center-income settings [18].

In Nepal in 2016, the median historic period at first matrimony is 17.9 years among women. 52% of women are married past age 18, every bit compared to xix% of men [nineteen]. The adolescent fertility rate has reduced from 110 per thousand women in 2000 to 60.v per chiliad women in 2017 [20]. The Nepal Health Sector Strategy 2016–2021 aims to reduce the adolescent fertility rate from 2.3 to 2.ane by 2021 [21]. However, the charge per unit of progress seems to be slow [22]. There has been global and national level advocacy to reduce the rate of adolescent pregnancy and notwithstanding in 2017, 120,000 adolescent were pregnant in Nepal [23]. Nosotros conducted this study to assess the incidence, risk factors, maternal and neonatal consequences among adolescent mothers in Nepal.

Method

The report has been reported as per the checklist for STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) [24].

Blueprint and setting

This is an observational study conducted for a menses of 12 months in 12 public hospitals of Nepal between July 2017–June 2018 nested within a large-calibration neonatal resuscitation program [25, 26]. These 12 public hospitals range from primary referral infirmary to secondary referral hospitals located beyond the country. The volume of annual delivery in each hospital ranged from thousand to 12,000 per year (Additional file ane).

All of these hospitals provided Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Intendance Services [27]. All the hospitals provided family planning, postnatal intendance and immunization services.

Eligibility criteria

All women admitted in the hospitals for delivery with gestational age 22 week or more were eligible to be enrolled in the report. Women consented to exist enrolled in the master study at the time of admission for delivery. Written consent was taken from the women. Women who gave nascency exterior these hospitals but were admitted for postnatal complexity intendance were excluded from the written report.

Data collection and management

To collect maternal and newborn health data, a surveillance system was established in all the hospitals, with data collectors collecting clinical data of mothers and newborns using a information retrieval form (Boosted file 2). In addition, a semi-structured interview was conducted with mothers at the time of belch to gather information regarding socio-demographic characteristics and antenatal care (Boosted file 3). Following the data extraction and interviews, the completed forms were assessed by a information coordinator on each site. Additionally, the information coordinator indexed the information sheets at the terminate of each day. Every calendar week, the completed forms were sealed in an opaque envelope and sent to the main inquiry office in Kathmandu. Forms were then quality checked for completeness. Data cleaning was performed in Census and Survey Processing System (CSPro) every month. The cleaned data were exported in Statistical Packet for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for data assay. The exported data were stored in a secured external difficult bulldoze to ensure the privacy and safety of the data. Personal data was removed before performing whatsoever data analysis. All hard copies of the data canvas were indexed and stored in a secured room at the research role for future references as per the ethical guidelines.

Variables included in the study

Socio-demographic and obstetric characteristics

Education level in mother was categorized equally formal instruction or not.

Ethnicity of mother was categorized equally Dalit, Janjati, Madhesi, Muslim, Chettri/Brahmin, and other castes based on hierarchical caste organization of Nepal [28]. Ethnicity was categorized as disadvantageous group (dalit, janjati and muslim) and relatively advantageous grouping (Madhesi, Chettri/Brahmin and other castes) based on hierarchical caste organisation of Nepal.

Severe anemia: the serum hemoglobin 7 1000 per deciliter or less at access.

Antepartum hemorrhage: vaginal bleeding before onset of labor [29].

Hypertensive disorder: classified by maternal diastolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 90 mmHg in 2 separate recordings [29].

Prolonged labor: cervical dilation that does not motility across iv cm after viii hrs of regular contractions, or cervical dilation lying to the right of the alert line on the partogram [29].

Preterm nativity: birth of the baby with gestational age less than 37 weeks. The variable categorized equally less than 37 week and 37 weeks or more.

Small weight for gestational age (SGA): birth weight less than x centile as per the gestational age [xxx]. The variable categorized as small weight for gestational age and appropriate weight for gestational age (10 centile or more).

Major malformation: major built malformation-malformation of neural tube defect, cardiac and gastro-intestinal.

Antepartum stillbirth: delivery of any fetus occurring subsequently 22 weeks of gestation or with a birth weight more than 500 thou that had with no FHS at access and no signs of life at birth.

Intrapartum stillbirth: delivery of a fetus occurring after 22 weeks' gestation or with a birth weight 500 g or more, who had FHS at admission and no signs of life at nascence.

Pre-discharge neonatal mortality: neonatal death before belch from the infirmary.

Statistical analysis

Differences in the demographic, obstetric and neonatal characteristics between the boyish and adult mother was assessed using the Pearson'southward chi-squared test (χ2). Variables which had a departure of p < 0.xx, was included in a multi-variate logistic regression assay. During data analysis, missing values were treated as missing. All the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.

Results

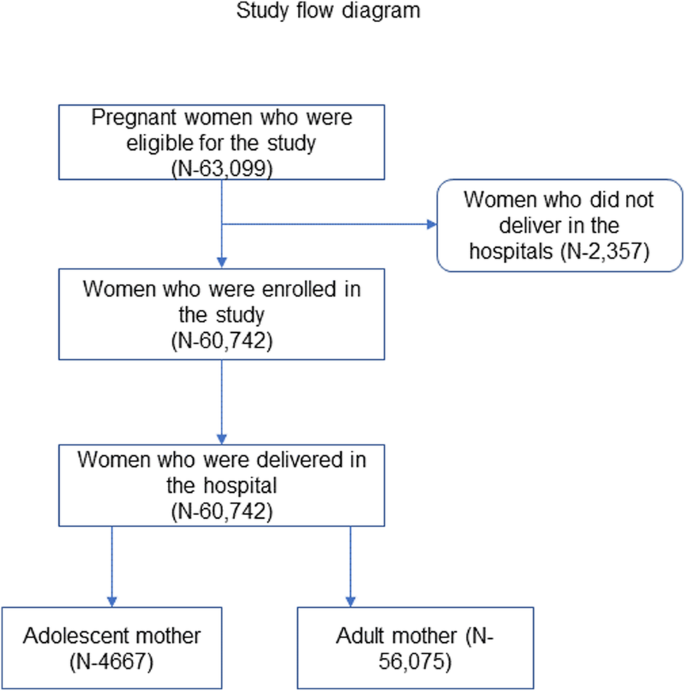

A total of 63,099 pregnant women admitted in the participating hospitals were eligible for study inclusion. Among these, 60,742 women delivered at the respective hospital and were enrolled. Among the enrolled women, 7.8% were adolescents (Fig. 1). There was a higher proportion of women from a disadvantaged ethnic group among adolescents compared to adult women (66.1% vs 47.8%, p-value < 0.001). More adolescent mothers lacked formal didactics compared to adult mothers (32.half-dozen% vs 14.2%, p-value< 0.001). (Tabular array i).

Study flow diagram

Results indicate that in that location was college proportion of poor medical complications and conditions among the adolescent mothers. Adolescents had more prolonged labour compared to adult mothers (i.iii% vs 0.eight%, p-value = 0.001), the prevalence of babies born with minor weight for gestational age was higher amongst the adolescent mothers compared to developed mothers (sixteen.4% vs 11.five%, p-value < 0.001), and the incidence of preterm nascence was college among boyish mothers compared to adult mothers (14.ane% vs 9.5%, p-value< 0.001). The share of babies born with major malformation was higher from mother who were boyish than developed (0.2% vs 0.one%, p = 0.009). Adolescent mothers besides had college intrapartum stillbirth rate than developed mothers (ten.0 per grand birth vs 7.0 per one thousand nascency, p-value = 0.039). Pre-belch neonatal bloodshed was higher among adolescent mother compared to amid adult mothers (2.0% vs 1.v%, p-value = 0.015) (Tabular array ane).

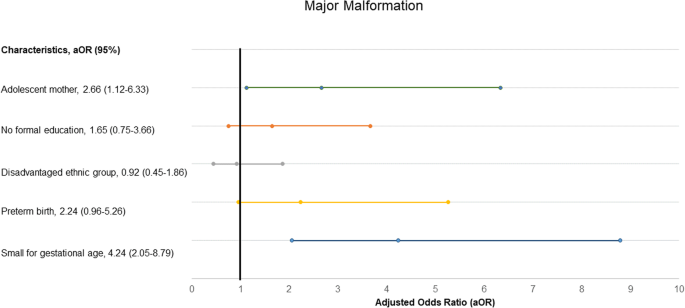

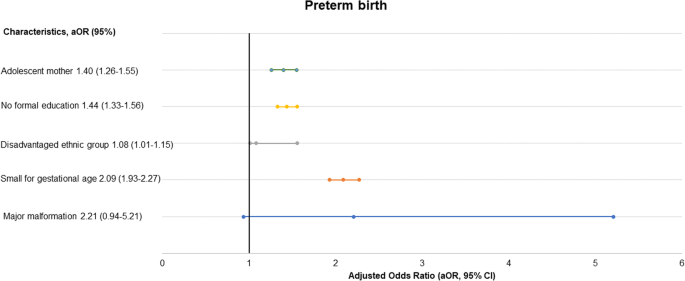

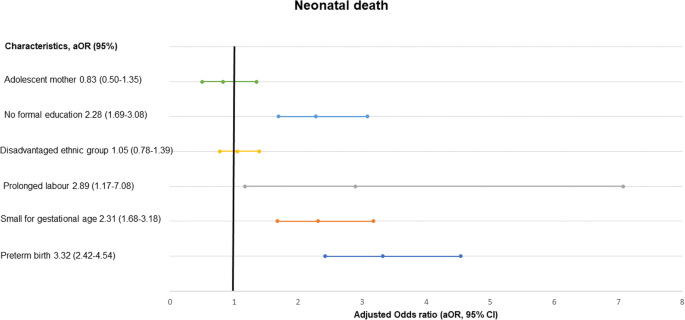

In the multi-variate assay, adolescent mothers had a 56% higher likelihood for prolonged labour than adult mothers (aOR- one.56, 95% CI, 1.17–2.10, p-value = 0.003) (Table two). Adolescent mothers had a 38% higher likelihood of having a baby beingness small weight for gestational age than adult mothers (aOR-1.38, 95% CI, 1.25–1.52, p-value< 0.001) (Table 3), and an almost 3-fold run a risk to have major malformation (aOR-2.66, 95% CI, i.12–6.33, p-value-0.027) (Fig. ii). Adolescent mother had xl% college likelihood of preterm birth compared to developed mothers (aOR-1.40, 95% CI, 1.26–1.55, p-value < 0.001) (Fig. 3). The boyish mothers had no significant association with pre-discharge bloodshed (aOR-0.83, 95% CI, 0.50–i.35, p-value = 0.44) (Fig. 4).

Level of association of adolescent maternity with major malformation

Level of association of boyish motherhood with preterm birth

Level of association of adolescent motherhood with neonatal death

Word

Results from this report indicate that women from disadvantaged ethnic group have a college likelihood of existence an adolescent mother compared to the advantaged ethnic group. Pregnant adolescents are at a college risk of adverse nativity outcomes compared to adult women being more likely to experience prolonged labour, preterm birth and having a baby that is small for gestational age. There was also an increased risk of having a baby with a major malformation among the adolescent mothers compared to adult mothers. Our results could however not notice any increased risk of pre-discharge mortality among babies built-in to adolescent mothers.

In Nepal, caste and ethnicity has been the heart-slice of the social bureaucracy [28]. Families from higher caste or relatively advantaged ethnic group are more likely to accept admission to education and wealth than in the lower degree or disadvantaged ethnic group. This access may be a preventative cistron for early union and adolescent pregnancy in the advantaged ethnic group. Furthermore, gender discrimination is relatively college among the disadvantaged ethnic grouping [31] . A longitudinal written report aimed to assess the factors for incident unwanted and unplanned pregnancies amid boyish women in Due south Africa showed that higher socioeconomic status was protective for both unplanned and unwanted pregnancies (OR 0.69; 95% CI 0.58–0.83 and OR 0.78; 95% CI 0.64–0.96) [32].

Adolescent girls who do not access education are also deprived of sexual didactics and information on the benefits to pregnancy, as well as the wellness consequences of early pregnancy [seven]. Girls who are better educated are shown to take greater decision-making power in relation to accessing and navigating wellness service [7]. Furthermore, adolescent girls in Nepal are more than likely to accept an adolescent pregnancy if they do not access education [31]. A cross-sectional study conducted amidst 457 women, age between 14 and 24 years carried out in Rupandehi commune of Nepal showed that lack of didactics for the girls was the central contributing factor for adolescent pregnancy [33].

Adolescent pregnancy has been associated with obstetric and neonatal complexity. A retrospective review of 15,498 pregnant women in South India has shown that girls anile ≤19 had higher incidence of anemia, depression birth weight, and a significantly lower incidence of caesarean sections/perineal tears in comparing to adult mothers [34].

Preventing first pregnancy and subsequent pregnancy among boyish female parent is important to reduce the morbidity and mortality [32]. Subsequent pregnancy amongst boyish mother is a major gamble that has implication for woman'southward life [32]. Therefore, strategies to prevent offset and subsequent pregnancies among adolescent women is critical. Education has become a major strategy in addressing adolescent health problem and it is worth investing to increase the extent and quality of schooling [35]. Investment in wellness and pedagogy not only play a disquisitional role in shaping the lives of adolescents in resource-poor settings, but it also has added benefits for generating high economic and social returns [36]. Therefore, investing in educational activity for girls in Nepal has broader ranging benefits for guild simply can also serve equally an artery to prevent adolescent pregnancies.

Methodological consideration

The study conducted rigorous surveillance to appraise the various demographic and obstetric factors among the adolescent mothers. I of the major strengths of this written report is inclusion of a large sample from 12 public hospitals located in different geographical locations in Nepal. Further, another strength of this study is inclusion of all in-built-in babies, including antepartum yet births.

Limitations

There are several limitations in the report. First, we conducted an interview at the time of discharge to gather information regarding socio-demographic characteristics and the quality of care. In that location might be interviewer's bias while gathering information. Second, we also could not interview mothers of still nascency which might have resulted in missing information. Third, though prior studies have shown association between pre-eclampsia and adolescent births, we could not explore pre-eclampsia every bit it might take been under-reported.

Conclusion

Reducing adolescent motherhood volition require investment in teaching of girls and access to information to forbid pregnancy. Considering adolescent pregnancy is associated with poor obstetric and neonatal issue, improving quality of intrapartum care for high-gamble mothers can reduce risk of poor outcomes. In Nepal, health facilities need to provide special attention and care for these high-risk mothers, to accost the health needs of adolescent girls and forestall long-term morbidities and mortality.

Availability of information and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are bachelor in the google drive repository https://bulldoze.google.com/drive/folders/17NOYhGln1hEUyE6_ihbzowSVQwnDH0hb

Abbreviations

- aOR:

-

Adapted odds ratio

- UNFPA:

-

Un Population Fund

- STROBE:

-

STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology

- CSPro:

-

Census and Survey Processing System

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Parcel for Social Sciences

- SGA:

-

Small weight for gestational age

- FHS:

-

Fetal heart audio

References

-

United Nations DoEaSA, Population Partition. Monitoring population tendency 2017. New York: Edited by Department of Economic and Social Affairs PD, Un; 2017.

-

Ki-moon B. Sustainability--engaging futurity generations now. Lancet. 2016;387(10036):2356–viii.

-

Editorial. Boyhood: a second risk to tackle inequities. Lancet. 2013;382 (9904):1535.

-

Blakemore SJ, Mills KL. Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annu Rev Psychol. 2014;65:187–207.

-

Resnick MD, Catalano RF, Sawyer SM, Viner R, Patton GC. Seizing the opportunities of boyish health. Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1564–7.

-

United Nations, editor. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York: Edited by United Nations DoEaSA; 2015.

-

Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, Ross DA, Afifi R, Allen NB, et al. Our future: a lancet commission on boyish health and wellbeing. Lancet. 2016;387(10036):2423–78.

-

Un Population Fund. Girlhood, non motherhood: preventing adolescent pregnancy. New York: UNFPA; 2015.

-

United nations Population Fund: world population prospects. New York: UNFPA; 2015.

-

Un Children's Fund: Un Children's Fund, 2012, Progress for Children: a report carte du jour on adolescents. New York: UNFPA; 2012.

-

Un Population Fund: Marrying Too Young: Stop Child Marriage. New York: UNFPA; 2012.

-

United Nations Population Fund: Country of Globe Population. New York: UNFPA; 2017.

-

United Nations Population Fund: Almanac Written report 2016: Millions of lives transformed. New York: UNFPA; 2016.

-

Azzopardi PS, Hearps SJC, Francis KL, Kennedy EC, Mokdad AH, Kassebaum NJ, et al. Progress in adolescent health and wellbeing: tracking 12 headline indicators for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016. Lancet. 2019;393(10176):1101–xviii.

-

United Nations: UN Secretarial assistant-General'southward Global Strategy for Women's, Children's and Adolescents' Health. New York: United nations; 2015.

-

Global Burden of Disease C, Adolescent Health C, Kassebaum N, Kyu HH, Zoeckler L, Olsen HE, Thomas K, et al. Child and boyish wellness from 1990 to 2015: findings from the global burden of diseases, injuries, and take chances factors 2015 study. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(6):573–92.

-

Gibbs CM, Wendt A, Peters S, Hogue CJ. The bear upon of early age at first childbirth on maternal and infant health. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26(Suppl 1):259–84.

-

Sychareun V, Vongxay Five, Houaboun S, Thammavongsa Five, Phummavongsa P, Chaleunvong K, et al. Determinants of adolescent pregnancy and access to reproductive and sexual health services for married and unmarried adolescents in rural Lao PDR: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;eighteen(one):219.

-

Ministry of Health and Population NE, ICF-MACRO. Nepal demographic health survey 2016. Kathmandu: Gon; 2016.

-

Ministry building of Health and Population, New Era: Nepal Demographic Health Survey. Kathmandu: GoN; 2002.

-

Ministry of Health and Population, New Era: Nepal Wellness Sector Strategy 2016-2021. Kathmandu: GoN; 2016.

-

Ministry of Wellness and Population, New Era: Mid-term review-Nepal Health Sector Strategy. Kathmandu: GoN; 2019.

-

Girls Not Bride: The Global Partnership to Stop Child Wedlock-Strategy 2017-2020. London: Girls Not Brides; 2017.

-

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger G, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) argument: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1495–9.

-

Kc A, Bergstrom A, Chaulagain D, Brunell O, Ewald U, Gurung A, et al. Scaling up quality improvement intervention for perinatal care in Nepal (NePeriQIP); study protocol of a cluster randomised trial. BMJ Glob Wellness. 2017;2(3):e000497.

-

Kc A, Ewald U, Basnet O, Gurung A, Pyakuryal SN, Jha BK, et al. Effect of a scaled-up neonatal resuscitation quality comeback package on intrapartum-related mortality in Nepal: a stepped-wedge cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2019;16(9):e1002900.

-

WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, AMDD: Monitoring emergency obstetric care, a handbook. Geneva: WHO; 2009.

-

Subedi One thousand. Degree organisation: theories and practices in Nepal. Himalayan J Sociol Anthropol. 2010;four:134–59.

-

World Health Organisation: Managing complications in pregnancy and childbirth: a guide for midwives and doctors. Geneva: WHO; 2000.

-

Lee Air conditioning, Kozuki N, Cousens S, Stevens GA, Blencowe H, Silveira MF, et al. Estimates of burden and consequences of infants born modest for gestational age in low and middle income countries with INTERGROWTH-21(st) standard: analysis of CHERG datasets. BMJ. 2017;358:j3677.

-

Langer JA, Ramos JV, Ghimire L, Rai Southward, Kohrt BA, Burkey Medico. Gender and child behavior problems in rural Nepal: differential expectations and responses. Sci Rep. 2019;9(i):7662.

-

Christofides NJ, Jewkes RK, Dunkle KL, McCarty F, Jama Shai N, Nduna M, et al. Gamble factors for unplanned and unwanted teenage pregnancies occurring over 2 years of follow-upwards among a cohort of young south African women. Glob Health Action. 2014;vii:23719.

-

Devkota Hour, Clarke A, Shrish S, Bhatta DN. Does women'south degree brand a pregnant contribution to adolescent pregnancy in Nepal? A study of Dalit and non-Dalit adolescents and immature adults in Rupandehi commune. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18(i):23.

-

Sagili H, Pramya N, Prabhu K, Mascarenhas M, Reddi Rani P. Are teenage pregnancies at high risk? A comparison written report in a developing country. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285(three):573–vii.

-

Sheehan P, Sweeny K, Rasmussen B, Wils A, Friedman HS, Mahon J, et al. Building the foundations for sustainable development: a case for global investment in the capabilities of adolescents. Lancet. 2017;390(10104):1792–806.

-

Malhotra A, Amin A, Nanda P. Catalyzing gender norm alter for boyish sexual and reproductive health: investing in interventions for structural modify. J Adolesc Wellness. 2019;64(4S):S13–five.

Acknowledgements

Nosotros would like to thank Omkar Basnet, database manager of Golden Community for information curation.

Funding

The primary study was funded by the Swedish Inquiry Council (VR), the Laerdal Foundation for Acute Medicine, Kingdom of norway, and Einhorn Family Foundation, Sweden. Funders had no role in the pattern, implementation and analysis of the study. Open up access funding provided by Uppsala University.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

RG conceptualized the study. AKC and RG analyzed the data and made the first articulation typhoon. PGP and AKS conducted the start revision of the data analysis. MM, NN, HZ, SS and SM reviewed the analysis and revised the manuscript. All authors agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ideals blessing and consent to participate

The main written report was approved by ethical committee at Nepal Health Research Council NHRC (reference number 26–2017). Written consents were obtained from all the participants included in the report prior to their participation in the study. Written consent was obtained from a parent or legal guardian on behalf of the participants under the historic period of xviii.

Consent for publication

Non applicable.

Competing interests

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Notation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits utilise, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in whatever medium or format, as long equally you give advisable credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Commons licence, and point if changes were fabricated. The images or other third party textile in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If cloth is not included in the article'south Creative Eatables licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will demand to obtain permission straight from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/iv.0/. The Artistic Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/i.0/) applies to the data made bachelor in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gurung, R., Målqvist, K., Hong, Z. et al. The burden of adolescent motherhood and health consequences in Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 20, 318 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03013-8

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/s12884-020-03013-eight

Keywords

- Adolescent mother

- Adverse outcome

- Preterm birth

- Major malformation

Source: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-020-03013-8

0 Response to "what is the best way to educate teenage pregnancy intrapartum"

Post a Comment